Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, April 23, 2022 for the “Remember When” column with the title, “When Frost almost got heaved.”

One hundred years ago, long before April would be designated as National Poetry Month or March as Women’s History Month, the following little known story offers an interesting intersection of the two. In addition, our still sometimes not-so subtle resistance to “outlanders” has been brought into sharp focus over the last few years and so it is always timely to look to history to see just how far—or not—we have come.

On April 17, 1922, Miss Fanny B. Fletcher of Proctorsville gave a lecture and poetry reading at Ludlow’s Fletcher Memorial Library. Miss Fletcher, who “spoke with the authority of one who had studied our Green Mountain poets well,” had been appointed by the Vermont Federation of Women’s Clubs to compile a list of potential state poet laureates. The “impelling motive” was that of “creating interest in Vermont verse.”

Miss Fletcher’s talk, titled “Poets of Vermont” and “interspersed with humorous anecdotes,” was a follow-up to the Free Public Library Commission’s publication of Miss Fletcher’s candidate roster. Newspaper articles about the upcoming election encouraged Women’s Clubs around the state to study the poets’ work and then vote for their favorite.

This action would start a debate neither Miss Fletcher nor Mrs. O. H. Coolidge, president of the Rutland Woman’s Club and originator of the idea, could have anticipated.

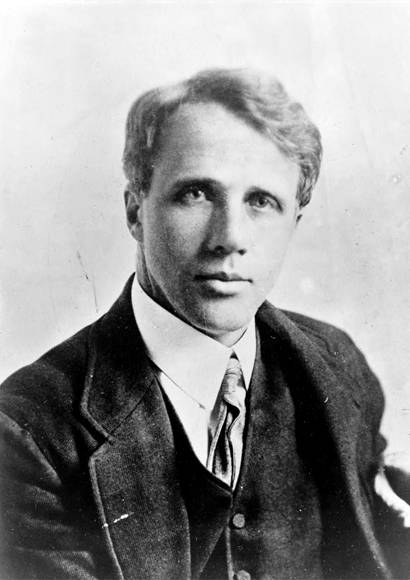

Rutland’s Women’s Club kicked off the voting, choosing Judge Wendell Phillips Stafford of Washington, Vermont as their choice for poet laureate. Robert Frost came in a close second. Over the following weeks, elections were held in other Women’s Clubs and on June 8, at the convention held in Springfield, the final vote was cast. Robert Frost was to be Vermont’s first poet laureate.

That Frost was a good poet was not argued. Instead it was that age-old argument over his Vermont roots, and Frost, a native Californian and sometime resident of multiple states, had none.

“Robert Frost is a real poet…” opined the Rutland Herald, “but he is not a Vermonter… We might as well elect Kipling on the strength of the fact that he used to have a summer home in Brattleboro.” The newspaper offered as more suitable candidates Judge Stafford and Daniel L. Cady of Burlington, as well as Manchester’s Sarah Cleghorn, who, they wrote, “is said to be something of a bolshevist but she can write real poetry.”

According to the Newport Express and Standard, Frost was an “Outlander.” “One would naturally suppose if a Vermont poet were to be chosen,” they wrote, “he would certainly be a native Vermonter, and not a mere summer resident.”

The Bennington Banner, however, took a more accepting stance: “Some people are Vermonters because they happened to be born here… Others are Vermonters because they elect to come here to make Vermont their home… Mr. Frost is a Vermonter of this second type.” The paper argued that since Frost lived—and voted—in the town of Shaftsbury, he was “duly and legally qualified to be the poet laureate of Vermont.”

While Frost’s degree of Vermontness concerned some, others attacked the process and progenitors of the election itself: The Women.

Unlike Miss Fletcher who was “deeply impressed with the fact that the election should be the result of the personal choice of each one of us,” the Newport Express and Standard saw it as an “expression of a small number of persons who spoke for themselves.” The Herald called Frost’s selection a “snap judgment” that “any chowder party or tea fight” could make. Barre’s Daily Times called the women’s election “merely a gathering of people” for a “little voting contest.”

The St. Albans Messenger quipped, “sometimes [women’s] minds are made up with more permanence than their complexions.”

Even so-called practical arguments against the election carried a hint of sexism. In a letter to the editor of the Brattleboro Reformer, a certain Mr. G.J. protested that the naming a poet laureate would be a “step backwards” and an “unnecessary expense” to the state. “The absurdity is too great to be countenanced by grown-up women usually classed as sensible.”

When in response to Mr. G.J. the Barre Times insisted that in fact the honor was “empty since it is without emolument in the financial sense,” Miss Fletcher saw through this “defense” of the Women’s Clubs. To her it was instead a “veiled suggestion that since the contest costs the state nothing it may be a good thing to let the women ‘go to it’ and thus work off some of their zeal for voting.”

Despite all the rigamarole elicited by the women’s “little voting contest,” it seems the Herald eventually accepted the decision. Or maybe not. An upcoming reading by Frost at Rutland High School was announced October 30th, 1922 under the headline, “Frost, Poet Laureate, Will Be Heard Here Wednesday.” However, the article itself stressed that Frost was poet laureate of the Vermont Federation of Women’s Clubs, not that of the state itself.

It would take another forty years for Frost to be officially recognized — i.e. by the predominately male members of the General Assembly — as Vermont’s poet laureate, giving him the unique distinction of being the second first holder of that title. Today, Mary Ruefle, another non-Vermont native, stands as our ninth official poet laureate.