Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, June 18, 2022 for the “Remember When” column with the title, “Female education: From the home to the school house“

Sampler made in Orange, Vermont, with text: “Made in school A.D. 1814 by Roxcinda Richardson”

(Vermont Historical Society)

1800–20

Early Vermont women were far from uneducated. In the 1770s, literacy among females is estimated to have been at 60%, and by 1820, over 80%. But most girls educated prior to 1800 could only expect to learn enough basic skills to become a proficient housekeeper.

When Miss Ida Strong opened a girls-only school in Middlebury in 1800, it was the first of its kind in Vermont. The idea of designing schools and curricula specifically for girls was progressive and marked the beginning of a nascent trend in Vermont’s female education.

Schools teaching “various branches of Female Education” including morality, and (among the upper classes) the ornamental arts of dancing, singing, needlework, etc., were essentially producing cultured wives and “Republican mothers” who would raise children to be virtuous members of society.

1820–30

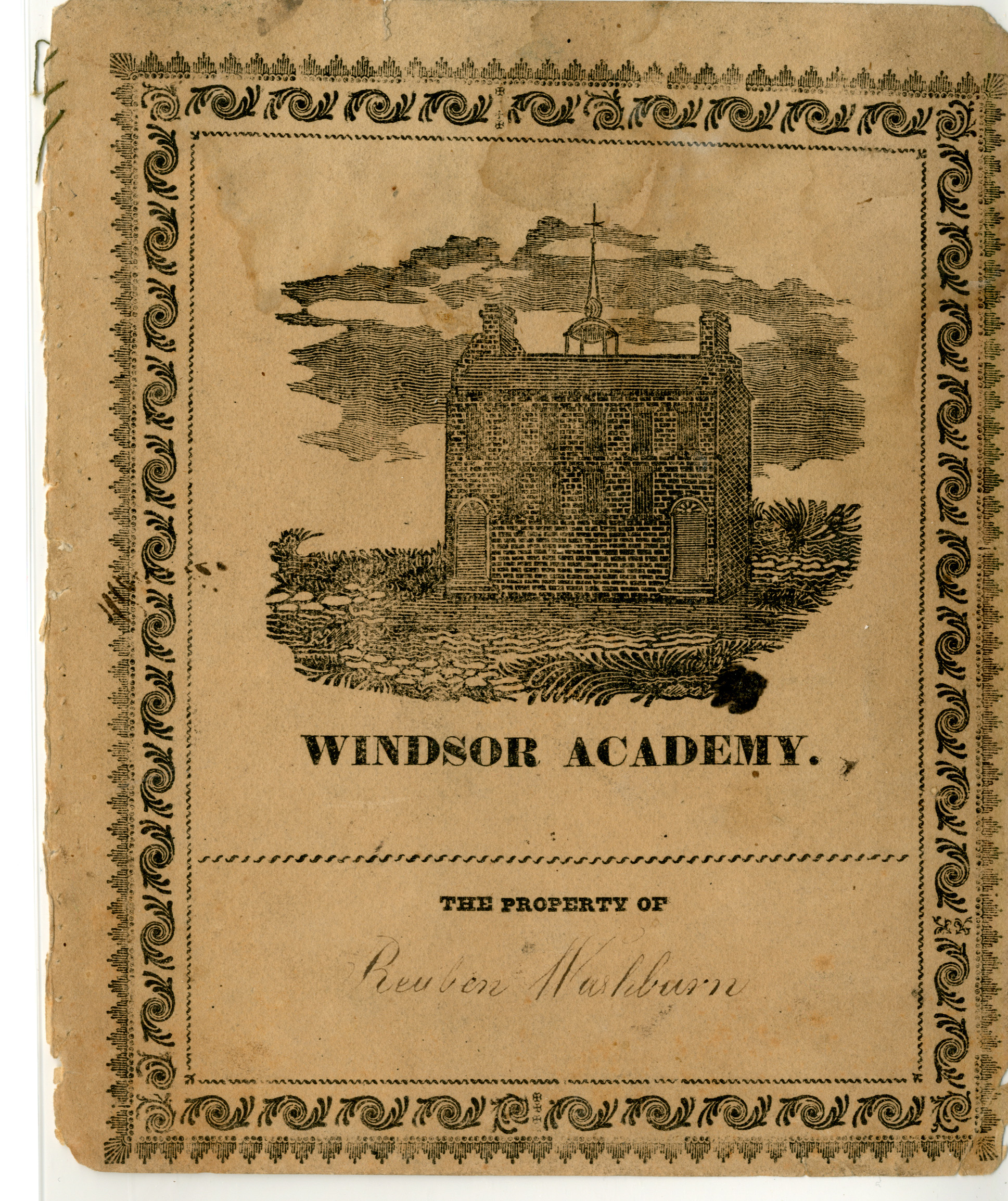

While many of Vermont’s grammar schools were co-educational by 1820, Emma Willard’s Middlebury Female Seminary and Windsor’s Female Academy, opened in 1814, were forerunners in the second phase in women’s education. As parents began to demand educations for their daughters that rivaled those of their sons, more girls-only secondary schools began to open.

Advertisements began popping up in every newspaper. Miss Bliss began a school for “young misses” in the village of Rutland. Mrs. Parsons opened an academy in Middlebury for the “reception and instruction of young ladies in the various branches of a liberal and accomplished education,” and the young women of Bennington were invited to attend Miss Jackson’s Female School in nearby Williamstown, Massachusetts. By the time Mary Palmer Tyler began running a girls’ school in Brattleboro with her daughter, Amelia, in the late 1820s, girls and young women were flocking to schools around the state.

And as these educated young women matriculated, some began teaching. Another shift was underway, including in the ideological debate over the nature of “women’s work.”

1830–40

In her 1835 “Essay on the Education of Female Teachers,” Catharine Beecher — nationally-known author, founder of Hartford (Connecticut) Female Seminary, and sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe — put forth an argument that women were uniquely qualified to teach, and it should be considered another of their “natural” domestic talents and duties.

While Vermont’s Emma Willard focused her campaigns on a woman’s right to an equal education, Beecher argued that the “natural” higher morality and ability to nurture made them ideal guides of virtue for the next generation. In this, Beecher was still essentially a proponent of the Republican motherhood ideal that came about post-Independence, her version merely expanded it out of the home and into the schoolhouse.

But in one area, Beecher differed from her forebears: For her, teaching was a way for women to gain hegemony. “Teaching should become a profession for women, as honorable and as lucrative for her as the legal, medical and theological professions are for men.”

Until 1830, the vast majority of teaching positions in county grammar schools were still held by men. But in the mid-1830s, when educators recognized that the women entering the profession needed some kind of formal training, Cavendish girls’ school began offering “normal” courses. Other schools quickly followed suit.

By 1840, female enrollment in schools already equaled or surpassed that of males around New England, and when the former Rutland County Grammar School became Castleton Seminary in 1846, women outnumbered men by as much as 3 to 1, many of whom were training to be teachers. By this time, approximately 40% of teaching positions in Vermont schools were held by women. In 1867, Castleton Seminary became the Vermont State Normal School and the rate of trained female teachers continued to rise.

As Beecher had hoped, the tide was turning — teaching was becoming “feminized.” She wasn’t the only one rejoicing at this fact.

1840s and beyond

In the 1840s, school reformers around New England were looking to establish a centralized, universal public school system. However, in order to convince towns and villages to adopt a system that took taxes out of their pockets, reformers had to prove to school boards they could afford it.

They needed female teachers. They were cheaper. (In 1847, a male teacher in Vermont earned on average $12.72 per month while a female was paid $5.32.)

Women were better suited for teaching because, the reformers argued, they are “less intent and scheming for future honors or emoluments.” (Here, we hear an echo of an opinion regarding women’s education written in 1800: “Occupations, which nature itself seems to have selected for the female, do not demand of her to ascend the sublime heights.”)

When the idea of paying women at all rubbed people wrong, the reformers played up the well-worn “ideology of domesticity.” Massachusetts’ Horace Mann, spearheading the reform movement, took Beecher’s image of the female teacher as “moral guardian of society” and further idealized her. He asserted women were “more mild and gentle” and “of purer morals,” and even went as far as maintaining women were better disciplinarians than men. Mann then took these generalizations of the feminine nature and touted them as qualities of the ideal teacher.

The plan worked. By 1880, 80% of Vermont’s teachers were female.

The state — along with the rest of the country — entered the 20th century with a new, and mostly mythicized, image and expectation of The Teacher (Miss Beadle, anyone?).

Very little has changed. The care and education of younger children is still largely considered and compensated as “women’s work,” and the idealized — gentle, nurturing — mother-teacher created first in the nursery and recreated in the schoolhouse over 200 years ago, endures as a cultural image.