Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, October 29, 2022 for the “Remember When” column with the title, Up to No Good

Cabbage Night was also known as Gate Night

“There is in every village and hamlet in America, a vulgar class of recreant mortals, who endeavor yearly to signalize the anniversary of ‘Halloween,’ by acts and deeds, more characteristic of devils than of boys or men.”

This moral outcry, published in the November 2, 1872 edition of the Middlebury Register, was in response to a “disgraceful scene” that had occurred that Halloween night. On Seminary Street in Middlebury, “the witches” had taken “gates off their hinges, and exchanged them for a neighbor’s gate… other gates were borne away to secret places.” Among “other annoyances too numerous to mention,” “door bells were rung.” Two cast iron lions were also taken from their perches atop a stone entryway and thrown in the mud.

Why were the boys up to such mischief, and why on October 31st specifically? To answer that question we have to take a whirl-wind journey through 3,000 years, give or take a few, beginning with the ancient Celts.

November 1st, or Samhain, marked the beginning of the Celts’ new year, when harvest celebrations included games (such as “apple-donking”) and fortune-telling. It was, they believed, a time when the “gate” between the worlds of the living and dead opened and spirits passed through eager to disturb livestock and damage crops.

On Samhain-eve, in order to appease these trouble-makers, food and wine was left outside the houses. Either to represent the spirits or disguise themselves as protection against them, the people went door to door collecting the treats while dressed in costumes or donning masks.

During the Middle Ages, many Pagan (and Roman) customs merged with those of the Church: Samhain was eventually replaced by All Saints Day (Nov 1) – All Hallows Day – and All Souls Day (Nov 2) when the dead were honored and evil spirits repelled. On All Hallows Eve bonfires were lit, the people paraded in costume, and the poor went “a-souling,” begging for “soul cakes” in exchange for prayers for the dead.

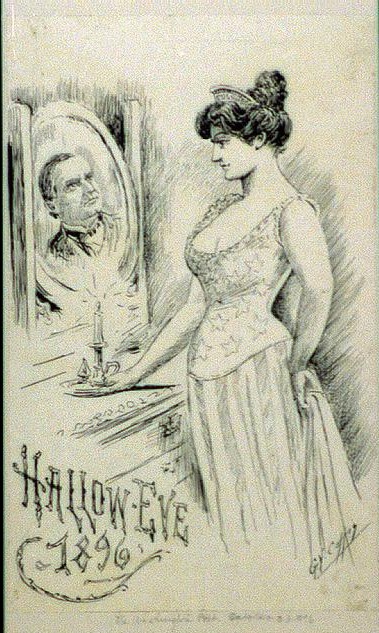

By the sixteenth century, in Ireland and Scotland in particular, where it was called Hallowe’en, the festivities had evolved into an event where costumed and turnip-lantern-carrying children went door to door “guising,” that is, performing party tricks in exchange for nuts, apples, ale, or money. Meanwhile, the adults gathered to tell stories of ghosts and trickster “fae” (fairies), and young women divined the time of arrival and qualities of their future husbands using cabbage roots, roasted nuts, or mirrors.

For obvious reasons, these Pagan-cum-Catholic practices and beliefs did not traverse the Atlantic Ocean along with the Puritans. As people of less austere faiths spread across North America, harvest festivals with dancing and fortune-telling were common, but Halloween celebrations as practiced in the British Isles for the most part did not make it to New England.

This was still the case into the early 19th century. In 1848, when the Vermont Patriot and State Gazette out of Montpelier relayed a Samhain legend from Scotland it was one of only four times, over a time-span of twenty years, that the word “Halloween” was mentioned in Vermont newspapers. Even then it was in relation to the traditions still practiced in Europe.

Then the Irish began arriving, bringing their traditions with them. As the number of immigrants increased, so did attention to Halloween. As a Rutland Daily Herald article in 1878 reported, “Tonight is Hallowe’en. Maidens who wish to investigate the future will walk backwards down the cellar stairs, holding in their hands the looking glass that is to reflect the features of the ‘coming man.’”

Just forty years later, over three thousand articles, party announcements, or advertisements were dedicated to the fun, “fashion,” and food – of the new-old version of All Hallows Eve.

Increasingly, however, the reports also included mischievous antics of local children.

While youngsters around the country were scaring people with carved turnips, smoking people out of their homes with burning cabbage stalks, putting livestock on barn roofs, and tipping outhouses on what was variously known as Gate Night or Mischief Night, Vermont kids (mostly boys) were celebrating our state’s version: Cabbage Night.

A 1879 report out of Montpelier describes that particular year’s scene: “Projectors and projectiles, cabbage head and cabbage stumps, were out in their usual strength and eloquence. Sundry strings were strung across sundry streets, sundry dooryards and lawn decorations were displaced, and nobody was killed” (which wasn’t always the case).

In an effort to curb the bad behavior, concerned parents and town organizers, like those in Rutland in 1922, hoped to “protect street lights, doorsteps and all other property” by holding a parade, dances, and parties. In fact, one of the first “Ghost Parades” in the country began in Bennington in 1905, which by 1916, according to one Miss Pratt, had “abolished rowdyism.”

But Miss Pratt was mistaken. “Hallowe’en has become a menace,” bemoaned a Bradford mother in 1946 upset about children “begging” for treats. The children should be “doing acts of kindness instead of demanding a bribe to be good.”

After trying to dissuade the pranksters with treats – which, after the phrase “trick-or-treat” was first coined in Canada in the late 1920s, became common in Vermont in the 1940s – Cabbage Night just shifted to October 30th. Windows were soaped, toilet paper strewn, and eggs thrown. Then candy was collected.

Such celebrations and “celebrations” kicked into high gear through the ‘20s and ‘30s and hit a peak in Vermont in the 1950s. During this decade, Halloween was mentioned in the state’s papers over 14,000 times. Twenty-six of these references were to the “vandalism” enacted throughout the state on Cabbage Night.

Over seventy years later, it seems Cabbage Night may finally becoming a thing of the past (references to Halloween-related vandalism in Vermont occur only twice in the entire 2000s). But there’s an irony here: the trick-or treating, the parades – like Rutland’s now-famous one with its dancing Day of the Dead “Skellies” – and costumes, were put in place a century ago in order (in part) to distract the trouble-making “fae” of our times. Surely this happened without conscious consideration of our ancestor’s similar customs. Samhain/Halloween is an ancient echo that has never ceased to resound.