Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, November 26, 2022 for the “Remember When” column with the title, Doing the Trot: Three Centuries of a Turkey Tradition

In February 1912, seemingly apropo nothing, a contributor to the St Albans Messenger quipped, “Vermont does not expect to see much of the turkey trot until just before Thanksgiving.”

If written in today’s paper, most readers would assume this statement referred to the popular Thanksgiving Day foot-race where turkey-costumed runners proactively burn the calories they will consume later that day. Although by 1912 the event that is now known as the Turkey Trot had been around for sixteen years (the first turkey-day race was held in Buffalo, New York in 1896) the race had not yet claimed the monika it holds today.

So, what was the St. Albans Messenger referring to? We can safely assume that contemporary readers would have understood it perfectly well. It was a pun. Because in 1912 the term “turkey trot” was going viral (so to speak).

Let’s start with the “trot” of actual turkeys.

Before refrigerated trains in the 1850s began delivering to Bostonians the sought-after Vermont centerpiece of their Thanksgiving dinner, the turkeys had to make their way down south some other way: alive and on foot. So, each fall throughout the 1800s, Vermont farmers and their families took to the dirt byways. Watching for predators – both animal and human – and scattering feed along the way, they “drove” thousands of turkeys towards the markets of Massachusetts.

And it was slow-going. After traveling not much more than ten miles each day, promptly at dusk, the turkeys flocked to the trees or any other high perch to roost, including, according to a 2014 VPR interview with Vermont Humanities Council’s then-chair, Peter Gilbert, on top of a school in Burke, causing it to collapse. In 1840, the birds alighted (a-heavied?) upon the surrey and horses of one unfortunate soul who happened to be passing by.

While some farmers used lanterns to encourage the birds to stay awake a little longer, covered bridges had the opposite effect. Many a roadway was blocked when the sudden darkness of the bridge tricked a flock into believing the day was done. When this happened, already exhausted farmers were forced to strong-arm the sleeping birds one-by-one back out into the daylight and on their way. The entire trip could take three weeks.

By the turn of the century, turkey drives weren’t as common, but not unknown. They were also not exclusive to New England. In some parts of the country, farms continued to deliver live birds to markets in time for Thanksgiving.

And so it was in 1912 in Cuero, Texas. According to the November 23 edition of the Rutland Daily Herald, spectators that year would have the opportunity to witness “a parade of 10,000 gobblers doomed to grace as many tables.” This particularly festive turkey drive, led by the state’s governor, was coined the “turkey trot” – a reference to The Big Scandal of the day, the latest craze among young people: a dance.

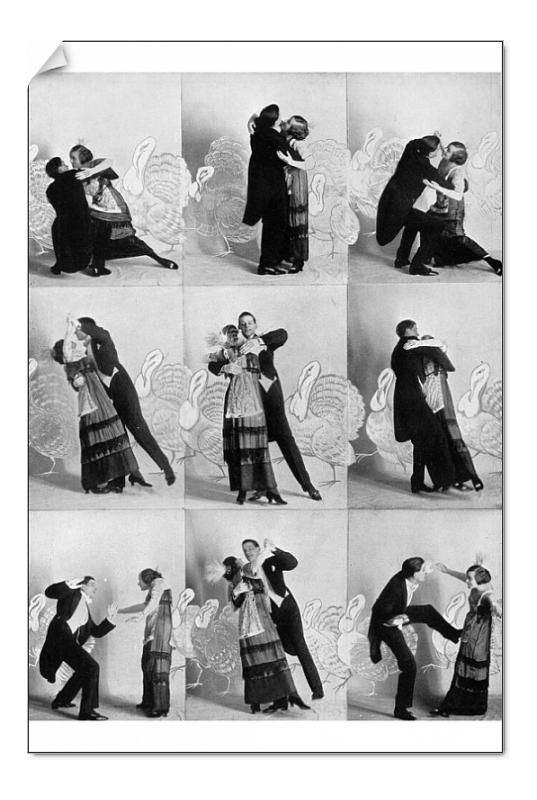

The “turkey trot” dance originated in California in 1909. Along with other ragtime “animal dances” like the Grizzly Bear and Bunny Hug, it had spread throughout the US by early 1912, becoming even more popular after it was performed in 1913’s Broadway show “The Sunshine Girl.”

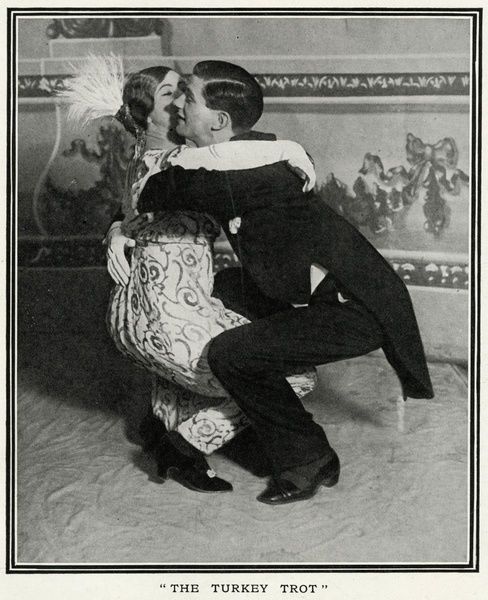

In the dance, partners slid and stepped across the floor face-to-face, their bodies held close – closer than many thought moral. To make things worse, dancers would bend at the waist (to varying degrees) and lift a foot in imitation of the dance’s namesake. Coinciding with the new century’s rising hemlines, the dance inspired such punnery as this in the February 14, 1912 Bennington Banner: “As we understand it from the pictures, the ‘turkey trot’ dance is one in which the turkey displays a good deal of white meat and only a little dressing.”

Society’s morality police were not impressed. In fact, in many states, some people found the dance so offensive that the real police became involved.

In one example, according to court summons quoted in a Library of Virginia blog post, a Newport News, Virginia theater owner was arrested and fined for performing, “…a wicked and scandalous, infamous and immoral, bawdy and obscene song and dance, or act, corrupting the morals of the public and youth, and too filthy, obscene and immoral to be in decency further described…”

In Vermont, the response was varied and not nearly as extreme. As reports came in from across the country of dance bans and even arrests of dance attendees, in January of 1912, in Barre, “the official ban” had not “as yet” been put on the dance. However, that same month, the St Albans Daily Messenger quoted a New York minister who claimed the dances were “forces calculated to awaken animal passion and to set youth on fire.” A writer to the Rutland Daily Herald, incensed by the “very insidious evil” of the “suggestive and frankly indecent” new dances, implored “the mothers of Rutland to hesitate before permitting their daughters” to learn them.

The voices of the ministers and mothers were apparently heard – in Montpelier, at least. That Thanksgiving – a once-popular time of year for dances – when a Boston man tried to initiate the turkey trot at an event, a member of the orchestra told him to “cut it out.” Meanwhile, some of the women “turned up their noses” and several others refused to stay in the hall “if the dance was allowed to go on.”

And so we can see that time has taken a phrase, as silly-sounding as “turkey trot” is, and hung onto it, for over a century. What began as a necessary “trot” down to the city with a herd of turkeys in time for city-dwellers’ holiday feasts, became a festive parade in Texas, which took on the name of a popular dance, and is now the name of a national-wide Thanksgiving day race. Maybe this Thanksgiving we should bring the other turkey trot back and dance off those calories after eating the poor thing.