Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, February 25, 2023 for the “Remember When” column with the title, The Right to Read and Savor.

This article was written in response to a plan to remove the majority of books from Vermont State College’s libraries. This terrible idea was — thankfully — eventually abandoned.

“A library is the nucleus of an educational facility… a college can only be as good as its library.” — Castleton State College Long Range Objectives Report, 1976

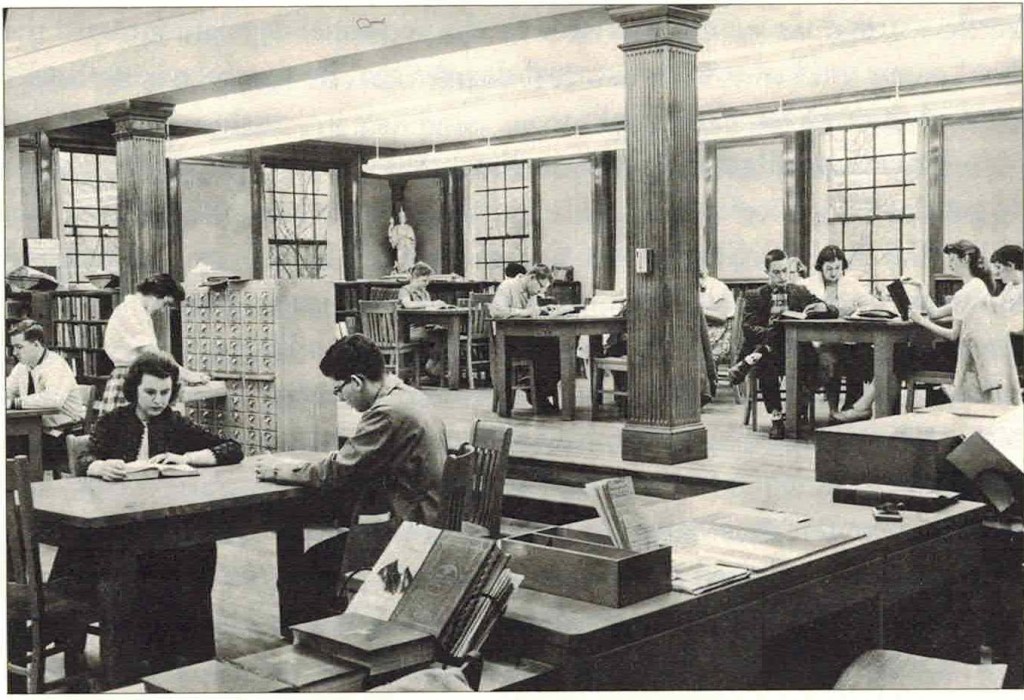

Students studying at Castleton State College’s Calvin Coolidge library in 1958

Last week I drove over to Castleton to my alma mater. I walked through campus, stepping over the plaques embedded in the path, each engraved with a name of the school, from Rutland County Grammar School in 1787 to today’s Castleton University. Even thirty years after I graduated, this still feels like home. Pushing open the door into the Calvin Coolidge library, I was filled with the same mixed sense of calm, comfort, and excitement as I had as a student. Surrounded by the intangible presence of knowledge, I spent many hours here studying, researching, browsing—learning who I was and wanted to be.

Michele, one of the incredibly helpful and knowledgeable Castleton librarians, showed me into the Vermont Room where the information I needed for this column is stored in file boxes, on shelves, and safely behind glass (including a green bound copy of my own History Honors thesis). There I sat for a few hours—and wanted to stay for many more—carefully leafing through the ephemera, much of which is priceless (and un-digitizable) pieces of Castleton’s—and Vermont’s—history: two hundred-year-old log books, one hundred-year-old course catalogs, faded photographs of Mercel-permed students, and mimeographed letters from the 1960s.

But probably one of the most amazing things I discovered was the transcript of a speech given on November 12, 1979 by Vermont State Librarian Patricia E. Klinck at the dedication ceremony of the new library addition (the two storey section). What made it so striking was just how uncannily prescient and pertinent her words were.

“I am sure we will soon see homes with computer terminals able to do banking, provide movies, dial up the grocery store, translate books, and on and on,” Ms. Klinck predicted with mind-blowing accuracy. “Some people may never leave their homes.”

Speaking to the role a library must play in the face of this “uncontrollable growth of information,” Ms. Klinck warned it must “channel its knowledge to allow all individuals, no matter where, rich or poor, to have the same right to information resources wherever the resources are located.”

“In a world where pendulums swing to extremes,” she continued, “the library must work to maintain balance.” Yes, people have “the right to quick access to current information from all over the globe,” but a library also needs to ensure that they “have the right to read and savor.” “The idea of curling up on a winter evening with my desk terminal is not comforting,” she said.

Today, we are facing what Ms. Klinck dreaded: the elimination of physical books.

Castleton was founded on the belief that a “respectable library” was as necessary to an educational institution as the “furniture, candles, [and] firewood.” According to the 1949 book, The First Medical College in Vermont, this provision written in the 1818 Articles of Agreement for Castleton Medical Academy, was unusual. Similar institutions created libraries only after being in operation for a while, whereas Castleton’s was an “early, if not first, provision for a library in the opening session of a medical college.” By 1826, Castleton Academy was boasting a “large and well selected library,” which, less than twenty years later, housed 3,000 volumes, a big collection for a country medical college.

In 1872, the “young ladies and gentlemen” of Castleton Normal School “desire[d] to supply the craving appetite, to close up the gaps in the ranks of the volumes.” The public was invited to help raise funds so that, “the life and service of the library may be greatly extended.”

By 1922, the small library housed in the Administration building had filled its shelves with the “latest works on education, psychology, history, books of reference, and general literature.” Then disaster struck. In 1924, the library was lost to fire. Less than ten years later, however, the library in the newly constructed Admin building (now Woodruff Hall) was bursting at the seams with 5,000 books. An additional library room was created in 1941 to house the still rapidly swelling collection.

Renamed Castleton Teachers College in 1947, the school continued to grow its library and hired a full-time librarian as required for accreditation. Enrollment boomed after it received this recognition in 1960, and soon Woodruff Hall could no longer hold its book collection. Calvin Coolidge library, “one of the most attractive, well-arranged college library buildings in the country” opened its doors in 1965.

However, Castleton State College (CSC) as the school was by then named, became a victim of its own success. In 1969, when the American Library Association recommended a college the size of CSC have 50,000 volumes, the Rutland Herald declared “Bare Shelves Crisis Confronts Castleton.” Not wanting to lose its hard-earned accreditation, CSC needed to buy approximately 18,000 more books. One letter dated October 31, 1969 addressed to the college faculty from the library director clearly shows the panic of that time: “WILL YOU KINDLY LOOK AROUND YOUR BAILIWICK and see if you CAN FIND EVEN ONE book on this list.”

Not even a year later, the library was already 7,000 volumes richer. An article in the college newspaper titled, “The Library Lives,” described the $5,300 raised by the students as “a graphic indicant of student concern.” By 1980, after the new wing was built, the library had doubled its collection with 70,000 books and 400 periodicals.

Today, boasting what the founders of Castleton Academy would most likely agree is indeed a “large and well selected library,” Castleton houses 134, 446 physical books and another 100,000 additional items.

Last week, sitting among some of the oldest and fragile of these items, it struck me hard that this could soon all be gone. These things that represent some of the quotidian details of a 236 year-old institution could disappear completely, leaving a void that future historians may no longer be able to fill. The stories beneath The Story could be left untold.

As Ms. Klinck said, “the availability of up-to-date information” does not guarantee a wise call “in judgment, interpretation, [or] action.”