Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, December 24, 2022 for the “Remember When” column with the title, When Holidays Were a Ball

Once upon a time, even here in little ol’ rural Vermont, in the 19th century, any time seemed a good time for a ball. However, the holidays – from Thanksgiving through New Year – were a particularly popular time. And in a time of rapid industrial growth, the expanding middle-class was eager to enjoy the kind of fun previously afforded only to the Old Rich.

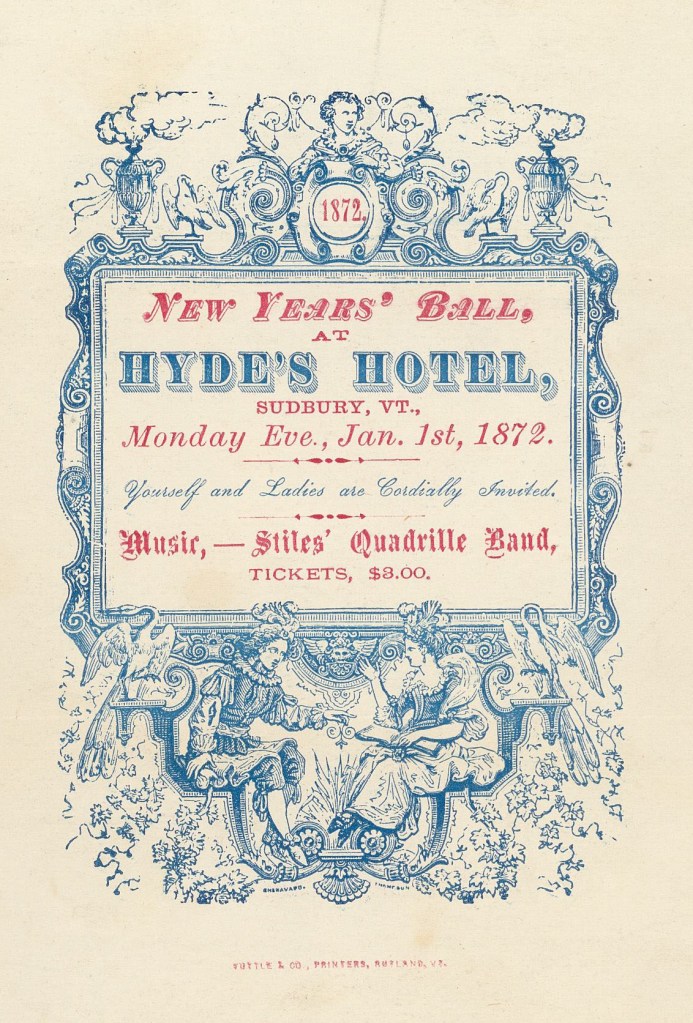

While private by-invitation-only balls and parties had been held earlier in the century – such as the ball held on Christmas Day, 1806 at Hyde’s Hall in Castleton – ticketed events open to the public weren’t generally known until mid-century. In fact, the first (known) advertised Christmas ball was in 1858. It was one of five “Anniversary Balls” listed in the Middle Register on December 15th, 1858 to be held at Hyde’s Hotel in Sudbury. (Some may recall the huge tumbling-down mansion on Route 30 just north of Hubbardton. This was the once-grand Hyde’s Hotel, or as it was renamed in the late 19th century, Hyde Manor.)

Christmas balls and social dances began popping up all over the state in quick succession. Starting with events in Lyndon and St. Albans in 1859, the number and locations steadily increased throughout the 1860s, reaching their height during the next decade. Hartford, New Haven, and Moretown were just a few of the towns holding holiday events in the 1870s, some of which became annual affairs. While many took place at hotels, some were held in Masonic halls or other large buildings, such as the armory in Rutland where the “Colored People’s Ball,” as it was advertised. was held in 1886.

And these dances were no small events. 80, 100, 130 couples were reported to have attended balls in Wallingford, Rochester, and Jonesville, respectively. In 1876, Danby boasted enough room for 200 couples to dance and mingle. And eat.

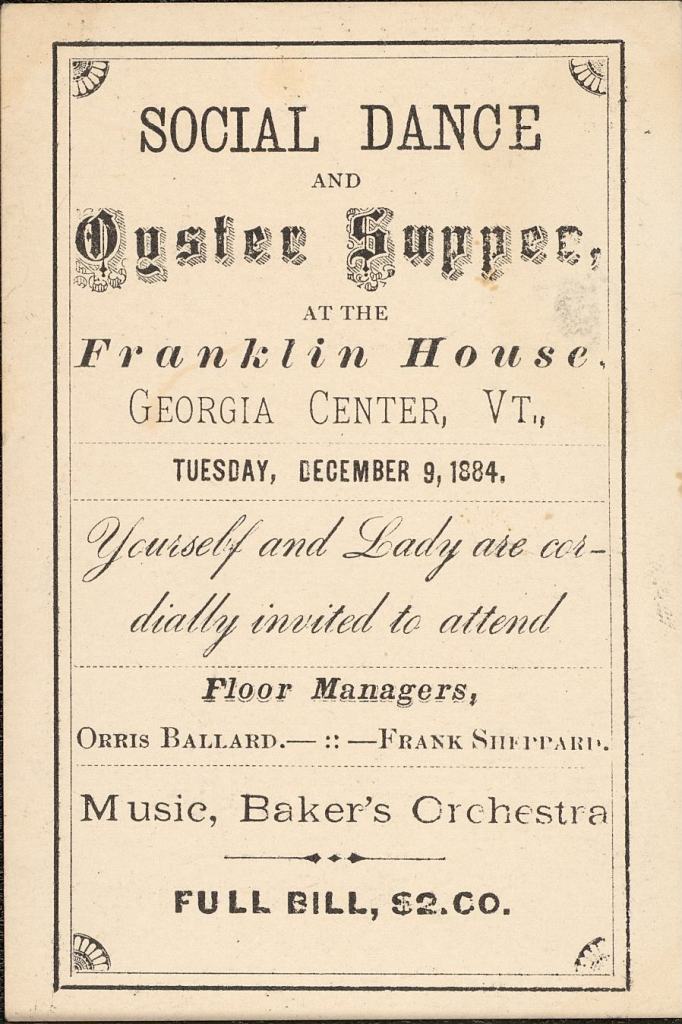

Increasingly throughout the 19th century, “social dances” and balls were also advertised as Oyster Suppers. Oysters were a staple – and favorite – for all socio-economic classes at the time. However, owing to the fact that in the winter, if transported in wet seaweed and straw, they could remain fresh for up to two weeks, they gradually became associated with the holiday season. After refrigerated train cars came into use in the later half of the century, oysters became even more popular. According to history.com, 700 million oysters were harvested in 1880 alone.

Alongside raw oysters in the shell, oyster pie, and myriad other oyster-based recipes the Victorians came up with, the refreshment table at a Christmas ball might include cold meats, crackers, cheese, cakes, fruits, nuts, and chocolates. Advertisements, such as one in the Argus and Patriot Hartford’s December 1871 ball, promoted the victuals with no lack of hyperbole: As well as the venue being “equal to the best to be found in the city or country, and vastly superior to most of them,” the supper was to be “doubtless… the best that can be had.”

It appears, however, from the many preserved event programs that the “supper” was not necessarily an event in and of itself, but rather a refreshment table located in a side room into which dancers could wander between musical numbers.

Dancing was by far the main event. With “the music superior” provided by the likes of the Holden Band, the Dandy Quadrille Band, Hatch’s Orchestra, or Hogue’s Band, couples would take the floor for a series of square (or quadrille), line (or reel), and circle dances (such as the waltz). A 1882 program from a ball in Wallingford, for example, lists the dances scheduled for the first half of the evening: Quadrille – Welcome, Quadrille – Plain, Contra – Money Musk, Quadrille – Lanciers, Polka Redowa, Portland Fancy, and Fisher’s Hornpipe.

As it was essential to one’s social standing and reputation – not to mention one’s chances of catching a suitable mate – anyone who was anyone had to know how to dance these various styles – and dance them well. To this end, numerous dance manuals were published throughout the 19th century, many by well-known, big-city dance masters.

But how to dance was not the only instruction in these manuals. Along with diagrams on how to do the German cotillon or Scotch reel, there were detailed “categories of precise rules which,” according to an article from the Library of Congress, “left nothing to chance.” Aimed at the new middle class, the manuals provided instructions on how to act in “good society.” Most often written for a female audience, they included rules of deportment, making light conversation, and other suitable party behavior (such as wearing a clean dress and not picking one’s nose).

Slowly declining in number through the 1880s and 1890s, by 1900, the popularity of such holiday festivities had dropped off drastically. Although Christmas dances became popular again in Vermont during the 1950s and ‘60s – exactly a century after the first wave of Christmas balls – after 1970 they gradually began to disappear again.

In the 21st century, most of us can only hope to imagine the lived experience of a “maze of crinoline and patent leather” that was a 19th century ball. Echoing an earlier history of such opulent dances, modern balls are rarely open to the general public. Organized as fundraisers or political events, they are once again mostly within the purview of the wealthy few.

But, that is also within the character of our times. Instead of socializing in large community groups we tend to hold smaller gatherings with family, friends, or co-workers. There are still places where one can square, line, or ball dance, but other than for a high school prom, dressing in one’s finest for an evening of dancing with all your neighbors is (sadly) a thing of the past.