Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, July 16, 2022 for the “Remember When” column with the title, A reverence for God, the hope of heaven, and a fear of the poorhouse

When Mrs. K. Lottie and her fourteen-year-old granddaughter were moved out of their cellar abode on Berlin Street, Montpelier, in February 1922, they didn’t go willingly. City officials, however, believed the two women would be better cared for on the town-managed poor farm on Elm Street.

As Mrs. Lottie and her granddaughter were moving into their new “home” forty miles away, William Seeley was setting himself free from his. The “straight as an arrow” 72-year-old was done with sleeping on a straw mattress in a building on Goodrich Road that used to house smallpox patients. Having “every inclination to work,” he went in search of a better life than the one he was living on Burlington’s poor farm. But soon Mr. Seeley found himself in jail – where “tramps and vagabonds” were often sent at the time – arrested for the crime of vagrancy. Suddenly, the poor farm may not have seemed so bad.

And by 1922, relatively speaking, it may not have been quite as bad as it had been during the prior century. Since their first appearance on the landscape, the conditions on the state’s poor farms were notoriously terrible enough to give rise to a colloquialism: Vermonters were said to be “raised with a reverence for God, the hope of heaven, and a fear of the poorhouse.”

As Andrew E. Nuquist wrote in a 1964 publication, Vermont’s poor houses and farms were “the last word in disgrace and for the aged, the poor, the diseased, the insane, and the crippled to be sent there was almost like receiving a death sentence.”

Growing out of Elizabethan England’s Poor Laws which replaced the previous “solution” of jailing, hanging, or indenturing the destitute and insane, Vermont’s laws requested that “the inhabitants of any town in this state may build or purchase a house of corrections or workhouse, in which to confine and set their poor to work. And such a house may and shall be used for keeping, correcting, and setting to work vagrants, common beggars, lewd, idle, and disorderly persons.”

Burlington opened its first poor house in 1816, Middlebury’s opened in 1822, Rutland established theirs in 1831, and the Sheldon poor farm began operating in 1834. Gradually, towns throughout Vermont were “caring” for – i.e. inadequately housing and often physically discipling – their most needy citizens.

Many “inmates,” as they were called, of Vermont’s poor houses and farms were permanent residents, some breathing their first and last breath within its walls. However, most were just temporarily down on their luck. Such as Mr. and Mrs. Dodge. This couple was forced to move to Montpelier’s farm in 1883 while they waited for Mr. Dodge’s pension, “which was taken away a year ago,” to be renewed. The number of short-term residents, such as unemployed young men and their families, tended to increase in the winter months after their heating fuel ran out.

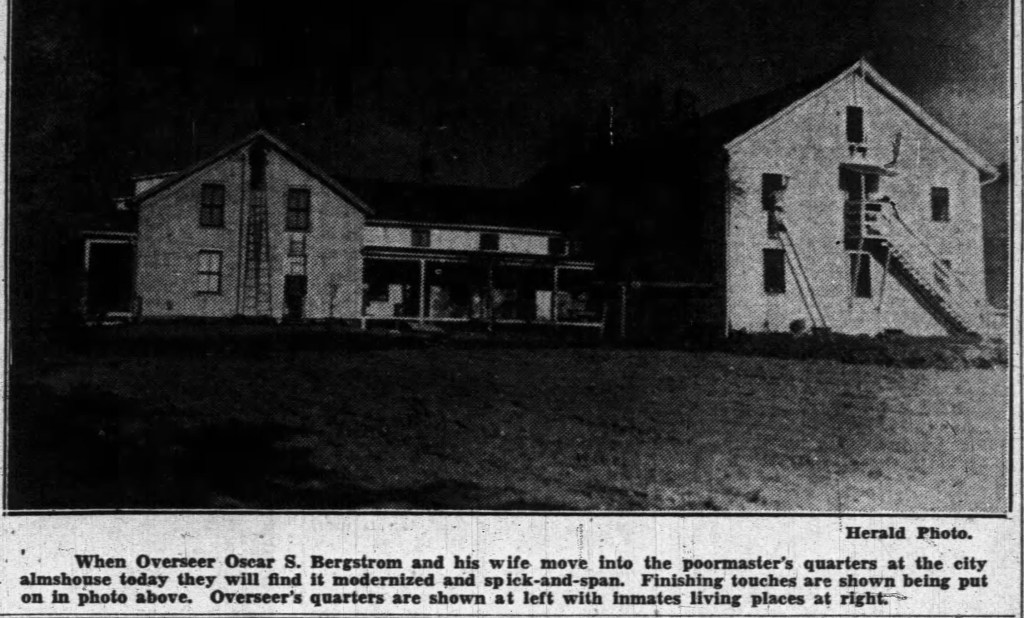

Strong-bodied residents were put to work on the land or maintaining the house, while those unable to work were provided food, clothing, and a roof over their heads.

While the overseers of some poor farms treated their charges better than others, the physical conditions were rarely optimal. Inadequate sanitation and bedding were common, and in 1916 alone, cases of tuberculosis were reported in Bennington, Colchester, Barre Town, and Hartland, syphilis was raging through Rutland, Woodbury, and Pomfret, and Plainfield was dealing with venereal disease.

K.R.B. Flint, a political scientist from Norwich University, was particularly concerned about the most vulnerable residents. As he reported in 1917:

“The conditions which exist in the poorhouses of Vermont must be characterized as very bad… [W]hen one sees the sick, the aged, the feeble‐minded, and children of tender years living together in confusion it shows that our system of public charity is fundamentally wrong… The sexes are not separated, the diseased are not segregated, and children are permitted by law to spend the years when environment is all important in an atmosphere which is nothing short of demoralizing.”

In response to Flint’s subsequent suggestions, Vermont passed a law in 1918 that prohibited children under sixteen to be admitted to poorhouses or farms. Children who could not be fostered out were instead sent to the Brandon School for the Feebleminded or the Vermont Industrial School in Vergennes. This was the first in a series of federal regulations, including charity organizations, such as the Red Cross, which allowed more people to fend for themselves and made way for institutions such as Rutland’s Old Ladies’ Home and Waterbury’s State Asylum. By the 1920s, the state’s poor houses primarily served those who did not qualify for these other establishments.

Starting with Hartland in 1938, one-by-one throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Vermont’s poor farms closed. Bookended by Rutland and Sheldon Springs’ comparatively late closings in 1966 and 1968, respectively, the 1967 Welfare Act officially signaled the end for Vermont’s poor farms. Responsibility for the poor, elderly, and infirm was removed from individual towns and taken over by the state.

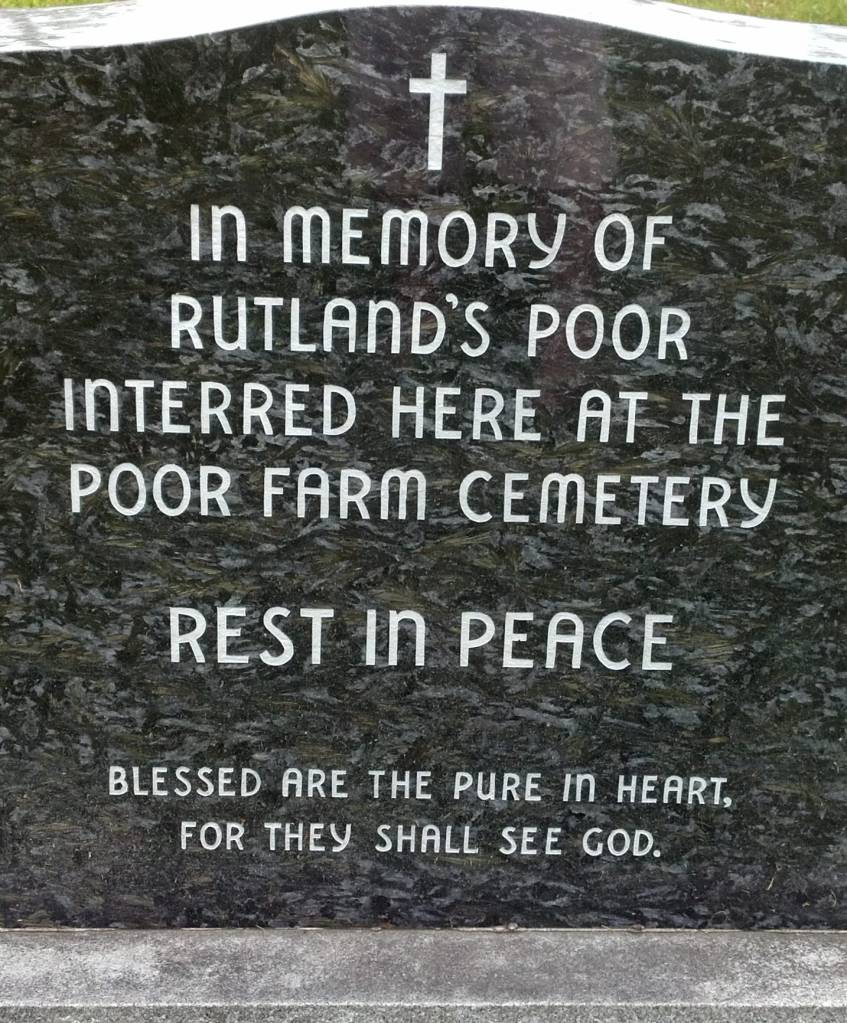

Today, the only hint at this chapter in our history is the occasional grown-over cemetery* and those signposts scattered throughout the state pointing down Poor Farm Road.

* I have written quite a few articles for the Rutland Herald/Times Argus on the poor farm cemetery discovered in Rutland which will posted at a later date. However, an introductory one can be found here: https://rutlandwhen.wordpress.com/2014/06/18/rutlands-poor-farm/