Middlebury College Special Collections, Middlebury, Vermont

Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, March 25, 2023 for the “Remember When” column with the title, Capturing literary history

One day in the early 1930s, up the mountain road in Shrewsbury chugged an open-top car. Coming to a stop at Pierce’s Store, a middle-aged woman stepped out and warmly greeted Mrs. Pierce, the store’s proprietor. The visitor was Helen Hartness Flanders and she was in Shrewsbury to capture a sound of the past.

Fifty years later, at age eighty-three, Marjorie Pierce remembered this day with a smile, the day Mrs. Flanders hauled a bulky dictaphone out of her car and asked her mother to sing into it.

Helen Hartness was born in 1890 in Springfield, Vermont to Lena Pond and James Hartness, inventor and head of Jones & Lamson Machine Co. and governor of Vermont from 1921 to 1923. After graduating from Dana Hall in Wellesley, MA in 1909, Helen often traveled from Vermont to Boston to study music under the pianist and composer, Heinrich Gebhardt. When she was twenty-one, Helen married a business acquaintance of her father, Ralph Flanders, a mechanical engineer, and eventual US Senator.

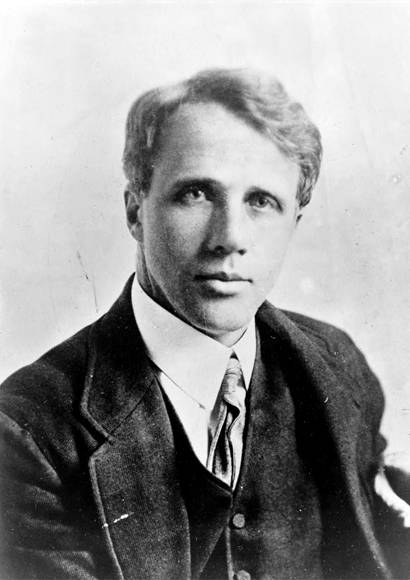

Helen was not just a gifted musician but also a poet. Mingling with Springfield’s literary elite at her family’s home, Smiley Manse, where Robert Frost and Dorothy Canfield Fisher were among her guests, she soon caught the attention of Vermont’s higher ups.

Read more: Helen Hartness Flanders: Contributing to the literary history of our stateIn early 1930, Gov. George Weeks asked Helen to join the committee on Vermont Traditions and Ideals, a branch of the Vermont Commission on Country Life (a program which grew out of Prof. Henry Perkin’s Eugenics Survey). Made Chairman of the Vermont Songs Survey, she became part of a team tasked with creating a four-volume collection of Vermont prose, poetry, biography, and folklore.

With the rise of radio, interest in traditional music had waned throughout the previous decade. As the last generation of ballad singers began to die out, there was concern that this aspect of Vermont’s history—what Helen called “hand-me-down singing”—would soon be lost.

Helen spent most of the first summer researching and writing letters and articles to newspapers around the state asking for the public’s assistance in her important mission. “What I have come upon in our State shows me that Vermont, which we all know has a way all of her own in growing scenery and men, has an equally distinguished way of growing her music,” she wrote to the Burlington Free Press. “Please search your memories and write to me.”

With letters with the names of those who still sang the old music starting to arrive in Helen’s mailbox, she and her partner, George Brown, a cellist and conductor of the Springfield summer orchestra could begin song collecting in earnest. Traveling with a thirty-pound wax cylinder dictaphone that ran off huge batteries carried in the back of the car, by October 1930, they had collected seventy-five songs just in southern Vermont.

Helen had a particular knack of coaxing songs out of people, writes Deborah Clifford, author of Remarkable Vermont Women, most of whom were over sixty-years-old, and often reticent to sing for a stranger. But, as Helen wrote in the introduction to her 1931 book, Vermont Songs and Ballads, by agreeing to do so, they “contribut[ed] to the literary history of our state.”

Searching at first specifically for “Child Ballads”—considered the oldest narrative songs originating in England—they ultimately collected many songs that were “very human stories that were made into song too far back in the generations to have any known origin.”

However, as Helen told attendees of the 1930 annual PTA meeting in Brattleboro where she shared some of her finds, there was “a flavor as particular to Vermont as any Kentucky mountain song had to that state.” Often these were “written to commemorate calamities or deeds of heroism,” the Springfield Reporter explained. One such song, sung for the PTA members by Josiah Kennison of Townshend, was “The Snow Storm,” a ballad about what came to be known as the Stratton Mountain Tragedy.

By the time the Commission’s funding ran out, Helen was fully hooked on song collecting, and partnering with Harvard musicologist, Phillips Barry, used her own money to continue the work she had fallen in love with. “The intangible, indescribable delights which went with the collecting of each song are not filed with them. These cannot exist in words,” she wrote in 1939. “Even that moment before driving out of the yard, with the dictaphone, address books, looseleaf notebooks, etc., on the seat of the car, cannot be distilled into the written word. Just beyond the windshield is the day-which one regards as untouched and undoubtedly undeserved (in the flurry of what is to be neglected at home)-so different each time, but always so electric with the unknown.”

Vermont didn’t make her job easy, however. Due to deplorable conditions of the back roads, collecting had to be suspended during winter months. Some of the old “songsters” on her list died before she could get to them. Each year she waited impatiently for the end of mud season. “To the folksong collector… spring is far more than joy in full-running streams and bird-songs,” she once said.

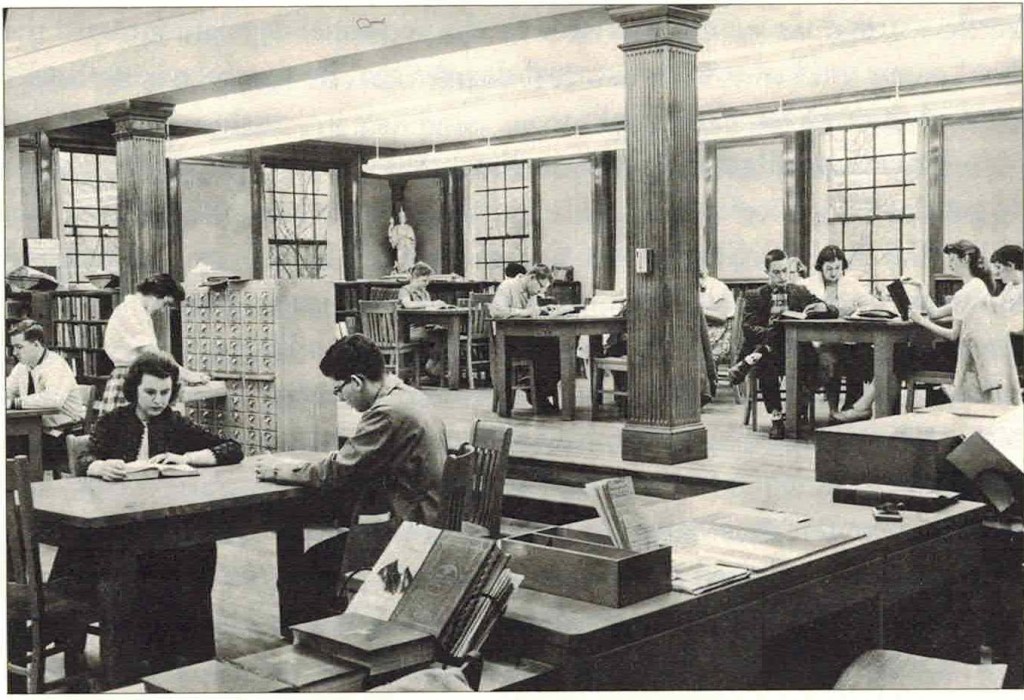

In 1941, when the slew of recordings and papers began overwhelming her home, Helen donated the collection to Middlebury College. (A year later, Middlebury awarded her an honorary MA degree.) Marguerite Olney, a graduate of Eastman School of Music with whom Helen had recently begun collaborating, curated the collection and took over the majority of fieldwork throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The two books the women ultimately co-authored brought Helen’s stack of published works on folk music to eight (in addition to her poetry volumes, a children’s play, and bylines in newspapers throughout New England).

Despite living in Washington DC for stretches of time over the twelve years her husband held office, Helen continued to work on the collection. In fact, with Marguerite’s help, the mission expanded beyond Vermont’s borders. Gathering religious, children’s, and popular songs, dance tunes and folktales from all around New England and New York, by 1958, the collection had grown to almost 5,000 recordings—including some performed by ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax—broadsides, hymnals, manuscripts, and transcriptions, plus several thousand books on American folksong, folklore, and balladry.

As Helen entered her twilight years, she spent most of her time home at Smiley Manse cataloging the collection. In 1967, her name was the first to be inscribed on Vermont’s Roll of Distinction in the Arts.

Just days after turning eighty-two, Helen—nicknamed the “First Lady of Springfield”—died. The poetess and balladeer, as her obituary called her, was remembered as kindly, modest, humorous, and hard-working, and was lauded as a woman with “tact, good sense and ability.” Her “most extensive knowledge of Vermont lore [was] perhaps more than anyone else in the state.”

Today, folklorists and musicians from around the world continue to consult the Helen Hartness Flanders Ballad Collection. The voices of yesterday can still be heard, the stories a reminder of Vermont’s past, captured in song.

The Snow Storm

The cold winds swept the mountain’s height,

And pathless was the dreary wild,

And mid the cheerless hours of night

A mother wandered with her child:

As through the drifting snow she pressed,

The babe was sleeping on her breast.

And colder still the winds did blow,

And darker hours of night came on,

And deeper grew the drifting snow:

Her limbs were chilled, her strength was gone:

“Oh, God!” she cried, in accents wild,

“If I must perish, save my child!”

She stripped her mantle from her breast,

And bared her bosom to the storm,

And round the child she wrapped the vest,

And smiled to think her babe was warm.

With one cold kiss one tear she shed,

And sunk upon her snowy bed.

At dawn a traveler passed by,

And saw her ‘neath a snowy veil;

The frost of death was in her eye,

Her cheek was cold, and hard, and pale;

He moved the robe from off the child,

The babe looked up and sweetly smiled!