Originally published in the Times Argus/Rutland Herald Weekend Magazine, October 28, 2023 for the “Remember When” column with the title, Hallowed Apples

Today, apples aren’t generally associated with Halloween; fall, yes (it’s almost as if we are contractually obligated to go apple-picking this time of year), but apples are all together too un-scary for modern Halloween tastes. (Irony dictates that we must recall the scare of the 1960s and 1970s that first removed apples and other non-commercially-packaged goodies from trick-or-treat pails.)

However, apples and Halloween go way back. October 31 is the eve of Samhain, the Celtic New Year, a time of year when the veil between the worlds of the living and dead lifted. It has been also suggested by some historians (but not proven) that over the course of Rome’s occupation of Britain, two Roman celebrations — one, Day of the Dead, and the other in honor of the goddess of fruit, Pomona — commingled with the festivities of Samhain.

Burning bonfires and tying apples to evergreen branches to encourage the sun god to return, the ancients would also put food outside their doors to ease restless spirits. To avoid the spirits from recognizing them during the day, people wore masks, or in other cases, dressed up as them to collect food on their behalf. By the 16th century, especially in Scotland and Ireland, this ritual had evolved into children going “guising,” that is, dressing up in costumes and going door to door asking for food. Even into the 1960s, Irish children were asking their neighbors, “Any nuts or apples?” In some parts of Canada children used to say, “Halloween Apples” instead of “trick-or-treat.”

(Author’s aside: I had never trick-or-treated until I moved to the US in 1985. In the UK, November 5th — Bonfire Night or Guy Fawkes Day — was the time for bonfires and apple-bobbing. Ironically, dressing up or trick-or-treating on Halloween didn’t become A Thing until after the movie E.T. introduced Brits to the idea in the 1980s.)

It’s no great mystery why apples might be associated with this time of year: fall is when the apples are ripe. Apples are not only the last crop to be harvested but also the most versatile, and for our ancestors, especially here in the cold North, they were a life-source. Eaten straight off the tree, cooked into baked goods, dried for later use, preserved as apple butter, fermented into cider, or fed to the pigs, from fresh to rotting, apples were (are) the fruit that keeps on giving.

For this reason, an affinity with apples also made sense mystically to the ancients. As the last food-source available before the land became barren once again yet “living” through the winter in its various iterations, apples have always been associated with immortality. And as their spring blossoms herald renewed life, their womb-like nature — round with seeds at the center — also symbolized fertility and love. As Samhain was a time when our ancestors looked to the future, apples also became central to fortune-telling rituals and games for thousands of years. Here are a few favorites from the 18th century:

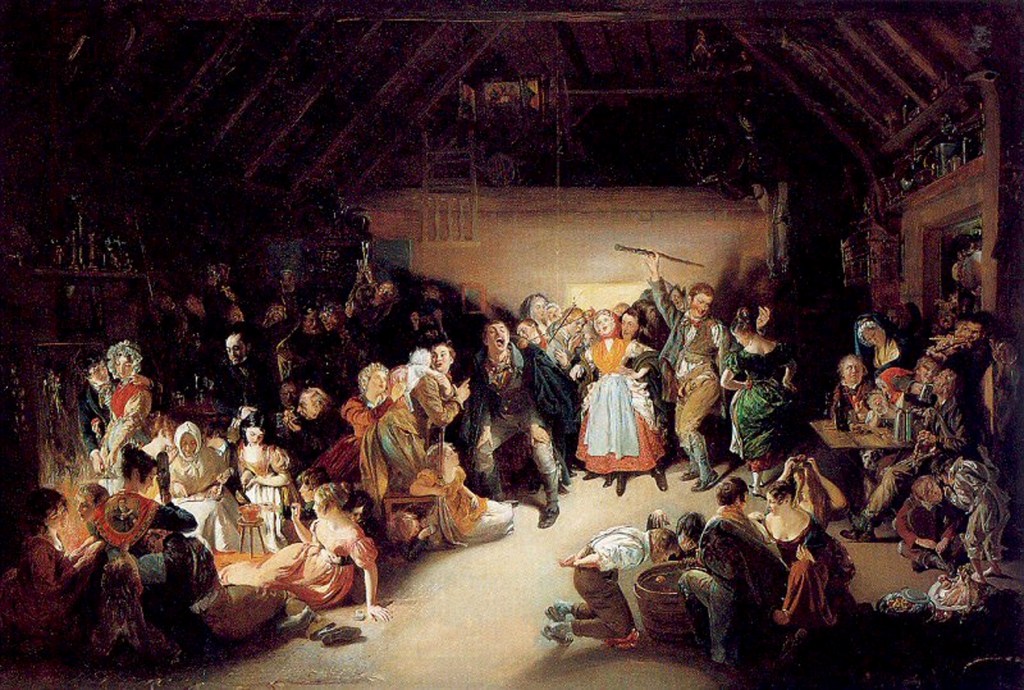

Snap Apple: Two sharpened sticks, tied into a cross-shape and with an apple and a burning candle stuck on opposite points, were hung from the ceiling. When the contraption was set in motion, unmarried men and women, hands behind their backs, took turns trying to catch an apple in their mouth. Winning determined who was to marry first.

Apple-bobbing (or donking): Young women would secretly mark their name on an apple which was then set afloat in a tub of water. Bachelors would then try to retrieve an apple with their mouth. The name on the procured apple predicted which of the girls he would marry.

Apple-peel throwing: While preparing apples for their various uses, girls would try to peel the skin in one continuous ribbon. The peeling was then thrown over the shoulder and the shape in which it landed supposedly formed the initial of her future husband.

While the Puritans didn’t bring such “heathen” ideas to America, Celtic/British traditions eventually made their way to New England with the Irish in the mid-19th century. Snap Apple doesn’t seem to have spread outside Vermont’s immigrant communities since there is no mention in the newspaper archives of the game outside of stories about the “Old World.” However, a safer version, where party-goers try to bite into a donut hanging from a string, did survive even into this century.

Fortune-telling was still part of Halloween party fun in the early 20th century, but, as the Bennington Banner proclaimed, “the revelers of 1912 scorn the old tricks carried out with apples, nuts, and the like and have invented new fun this year.” Instead, young ladies would peer through holes cut in a sheet to guess the male peeking through from the other side, or, as a 1927 article from Groton describes, gathered in a dark room, girls picked their “future husband, or second, as the case should be,” by correctly identifying that man’s silhouette on the other side of a sheet.

Apple-bobbing is the only age-old game that has remained in the modern consciousness. While maybe not a common element of Halloween parties today, it still shows up as a form of entertainment at some fall festivals. Thankfully, marriages are no longer dependent on the results.

These celebrations may be a world apart from the aesthetics and antics of a modern Halloween — a sight no ancient fortune-seeker could have ever predicted — but at our many annual apple and cider festivals, Vermonters still honor the ever-amazing apple that helped get generations of our ancestors through the winter.